Endless Possibilities for Superconductivity

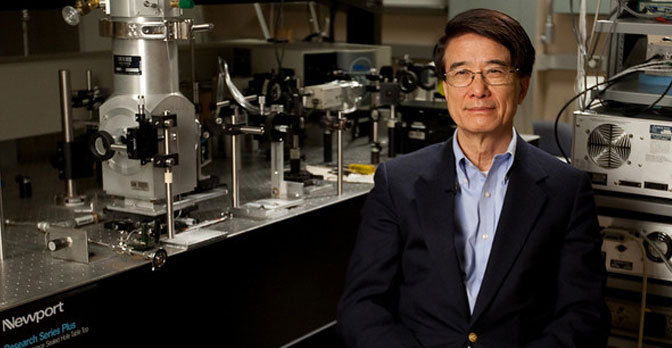

When C.W. “Paul” Chu came to the University of Houston in 1979, the superconductivity pioneer imagined limitless possibilities.

After a stint conducting industrial research at Bell Laboratories and serving as physics professor at Cleveland State University, Chu was looking for a place to really delve into his research. He found it in Houston.

“The time I came, that was the boom time of Houston, and nothing seemed to be impossible in Houston,” he said. “That is why I came here.”

The decision paid off. In 1987, Chu, together with colleagues, made a discovery that would usher in a new era in materials science. With the discovery of superconductivity above 77° Kelvin, the boiling point of liquid nitrogen, Chu opened the door to major energy breakthroughs.

Superconductivity is a subfield of condensed matter physics. A superconductor is a unique material that loses its resistance to electricity when you cool it below a certain temperature. Superconducting materials are now being used to make devices for energy generation, transmission and storage, as well as ultra-fast and ultra-sensitive signal detection and magnets for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

“In other words, superconducting transmission cables can be used to transmit electricity over long distances without energy loss,” he said. “Today, we use copper wire or aluminum wire which is less efficient, so superconductors can do wonders.”

Chu, who founded the Texas Center for Superconductivity at UH and now serves as it executive director, continues his research, hoping to achieve superconductive properties at even higher temperatures with minimal cooling necessary. He receives funding from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Department of Energy to develop new materials.

“Whenever you are doing any cooling, you are consuming energy,” he said. “So when you can get to the point where you are operating superconducting devices without cooling them, you change every aspect of our lives, wherever electricity is involved. That will induce an industrial revolution. It is very exciting.”

Chu’s interest in superconductivity developed when he was a graduate student, but even as a young boy growing up in Taiwan, he was interested in science and technology.

“Even when I was a little boy, I started making motors, generators, crystal radios, and so on,” he said. “All those small gadgets had a major impact on my later career.”

Chu completed his undergraduate education in Taiwan, and came to the U.S. to pursue his graduate work at the University of California at San Diego. That is where he met his advisor and mentor, Bernd T. Matthias, whom he described as “a giant in superconductivity.”

“Superconductivity is one of the few subjects in science that has intellectual challenges as well as the technological promises,” he said. “Therefore, it has attracted scientists from different fields, such as physics, chemistry, material science and engineering.”

The mentor relationship had a major impact on Chu’s future career.

“One of Professor Matthias’ major goals was to get superconductivity to work at as high a temperature as possible, and that has been my passion for the decades,” he said.

Chu is so passionate about superconductivity because he sees it as key to helping to solve the world’s energy problems. There are two ways to stave off future energy shortages – improving the efficient use of existing resources and developing new resources, including renewable energy, he said.

“Superconductivity can do the first part, which is making the use of energy more efficient,” Chu said.

Superconducting material also can be used in devices like fault current limiters, inserted into electrical grids to help prevent blackouts and brownouts during lighting strikes or other power surges, or for medical applications such as MRI machines, he said.

“If we can reduce the cost of the magnetic resonance imaging technology and improve its mobility, that would have a major impact on health care in the Third World,” Chu said.

For his work, Chu has been given countless prestigious awards, including the Comstock Prize, Bernd Matthias Prize, the Texas Instruments Founders Award, the Prize Ettore Majorana-Erice-Science for Peace and the National Medal of Science. He was named the Best Researcher in the U.S. in 1990 by U.S. News & World Report, and has been inducted into the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and other prestigious foreign academies.

The awards and recognition are nice, but Chu said it is his passion for his work that keeps him going – passion he likes to share with students.

“I tell them I work seven days a week, and more than 10 to 12 hours a day,” he said. “I don’t expect a student to do the same, but I never feel that it is very hard, because that is where my heart is.”

Chu enjoys working with students at the Texas Center for Superconductivity, which he said serves an important role in educating the next generation of scientists.

“I always like to see that they can develop a passion for the work we are doing,” he said. “Passion is extremely important.”

A passion for education took Chu to the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, where he served as president for eight years and two months while he simultaneously continued overseeing his research at UH until September 2009.

While in Hong Kong, he raised the international reputation of that institution as a world-class university – a similar effort that the University of Houston is undertaking in its pursuit of Tier-One status. Chu said he wholeheartedly supports the efforts to reach Tier One.

“Based on my humble opinion, this is the right way to go because you have to get the recognition from the outside world in particular, to know you are serious about hiring distinguished faculty members, and creating new knowledge,” Chu said. “The best faculty members attract the brightest students … that also attracts funding and recognition from the world. Therefore, having excellent faculty do cutting edge work is the best way to education students and help them as they graduate.”

Great improvements have already been made over the years since he arrived on campus in 1979, he said.

“We are getting more and more quality faculty members, and their work has been recognized by more and more people outside of Houston,” he said. “I think that is a good thing.”

The support of the community is also increasing, he said, adding that is key to UH reaching Tier-One status.

“I feel right now the city is fully behind the university,” Chu said. “I can see that President Khator’s vision for a Tier-One university is getting closer to reality.”