When Gov. Rick Perry announced that the state would give the University of Houston a multimillion-dollar grant-its first through the Texas Emerging Technology Fund (ETF)-some members of the audience swelled with pride, others exhaled after months of hard work to make it happen, and all of them watched one man accept the school’s colors and the planet of responsibility that comes with them.

Jan-Åke Gustafsson, an internationally renowned hormones expert, already had accepted an appointment over the summer to expand his revolutionary research efforts at UH. But, the $5.5 million grant from the state sealed the deal and will enable his team to create next-generation pharmaceuticals and medical technologies at a world-class center to be established by UH and The Methodist Hospital Research Institute (TMHRI).

The recruitment of Gustafsson, Foreign Honorary Member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and member of the Nobel Assembly, represents a significant milestone in fulfilling President Renu Khator’s vision for the university, which includes a UH Health Initiative that will expand UH’s presence and partnerships in the Texas Medical Center.

“We are delighted to have Dr. Gustafsson join our faculty as a key leader in our biomedical initiative,” says Khator. “He was courted by Ivy League institutions and determined the University of Houston offered the best opportunity to advance his research. He will play an important role in our quest for top-tier national recognition.”

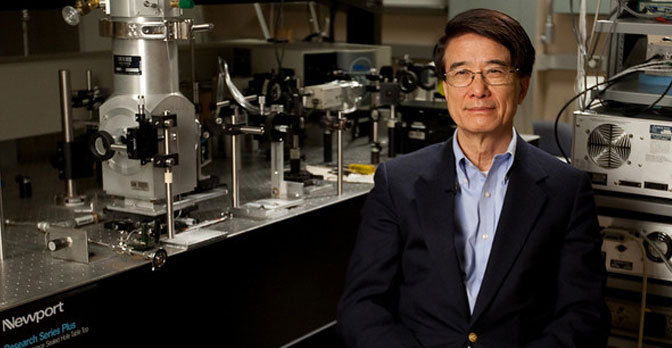

Gustafsson, who holds a Ph.D. and M.D., heads the Center for Nuclear Receptors and Cell Signaling. He teaches at the Department of Biology and Biochemistry and the Department of Chemistry in the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. He also will be a member of TMHRI.

His appointment is the first strategic hire for the UH Health Initiative and follows strategic hires for other UH “research clusters” since Khator arrived last year. His appointment includes a fifteen-member research team, which helps to “fast track” progress and innovation coming out of the new center.

“Often, new ideas and breakthroughs occur at the borders of scientific disciplines,” Gustafsson says. “It’s when they come together in the border zone that you can have new breakthroughs, new ideas-you can advance the field.”

Gustafsson says he looks forward to building a state-of-the-art research center, which will focus on a “medically very important field.”

“The concentration of outstanding scientists at UH, TMHRI, and in the Houston area in general, including the Texas Medical Center, provides unique possibilities for cutting-edge translational research with great clinical and commercial potential,” he adds.

Gustafsson is revered worldwide for his translational research on nuclear receptors, a class of proteins found in cell nuclei that capture hormone molecules and interact with and control the expression of genes. Research in the field is vital in developing treatments for such diseases as cancer and diabetes.

Here’s how nuclear receptors work: Each receptor in the cell’s nucleus has a cavity shaped just so that a hormone molecule can fit inside. Once wedded to the hormone, the nuclear receptor’s outer surface changes, depending upon the type of hormone housed within. Then, other proteins recognize the receptor’s surface structure and join in a chain reaction. This hormone-controlled process influences expression of genetic information and the development and metabolism of an organism.

“Nuclear receptors provide the lock that the key of your hormones fits in. They allow your DNA to be read and expressed,” explains B. Montgomery “Monte” Pettitt (’75, ’75, Ph.D. ’80), Hugh Roy and Lillie Cranz Cullen Professor in Chemistry and professor of computer science, physics, biology, and biochemistry. “Gustafsson discovered a major estrogen receptor protein and has worked in a variety of application areas, including cancer. We are very fortunate to have him and his team relocating to UH.”

Gustafsson’s research group at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, in the mid-1990s discovered the existence of a previously unknown estrogen receptor that plays a pivotal role in the function of the brain, lungs, and immune system.

Today, drugs are being developed to stimulate that receptor, named ER-beta, to battle a number of diseases, including breast, prostate, and lung cancers. In some instances, the abnormal cell division that creates cancerous tumors can be slowed down or stopped by stimulating the receptor.

“The approach we take with the ETF is different than you might expect from government. It’s not about a giveaway. It uses incentives, investments that lead to innovation here in Texas,” Perry says. “We’re about finding marketable technologies, fueling those innovations . . . starting ventures that turn a profit. You might say that the old academic motto of ‘publish or perish’ is being replaced by ‘patent or perish.'”

Perry says the UH grant is “the latest example of our efforts to find great ideas born in university laboratories, invest in them to generate the products that can ultimately create jobs, turn a profit-keep our state’s economy going.”

Gustafsson has a solid commercialization track record, and he is co-founder of KaroBio AB, a biotechnology company on the Karolinska campus, along with Dr. John D. Baxter, who joined TMHRI last year.

“Of today’s existing drugs, 20 percent are actually drugs that affect, as keys, these nuclear receptors,” Gustafsson explains. “It’s a vast area for further development.”

Dr. Michael Lieberman, director of TMHRI, says the center represents a substantial collaboration between UH and Methodist.

Birx says Gustafsson’s team will provide leadership aligned with UH’s mission “to engage the major issues of our time in ways that significantly impact the lives of those around the world.”

“His scientific and commercialization expertise will capitalize on and serve Texas’ desire to lead in medical discovery-particularly in cancer diagnostics and therapy,” Birx says.